Digital Alienation, Rentier Capitalism And The Rise Of Techno-Feudalism

Delivered at NPSSH 2017, Maynooth University.

There are many people who will point out the advantages brought about through technical innovation and who will sing the praises of new technical capabilities. My aim is to look for, and evaluate, the negative consequences of technical innovation. In particular, I take aim at those who confuse the mere creation of new technical capabilities with moral good.

In considering the undesirable side of digital technology, I seek to identify the key characteristics which enable negative effects. Here I take the approach of Critical Theory. I regard the quality of life of the individual as the primary moral assessment of any society.

Central to my presentation is the concept of progress.

We can trace the origins of the concept of progress back to Enlightenment thinkers who held that empirical scientific research would inevitably lead to political innovation. They supposed this would, in turn, lead unavoidably to an improvement in the quality of life of all humans. This was based on a belief that there existed objective ethical values which could be determined rationally – through the development of scientific knowledge and rationalist methodologies.

By the mid-19th century, it was almost universally accepted that technological innovation was a necessary condition for progress. For many, technological invention was, in and of itself, sufficient to trigger improved social and political conditions. For them, technological innovation had become identical with progress.

The mood of the times was summed up in 1847 when US Senator Daniel Webster opened a new section of the Northern Railroad with the following words:

“It is an extraordinary era in which we live. It is altogether new. The world has seen nothing like it before. … everybody knows that the age is remarkable for scientific research into the heavens and the earth… and perhaps more remarkable still for the application of this scientific research to the pursuits of life. The ancients saw nothing like it. The moderns have seen nothing like it till the present generation. . . . We see the ocean navigated and the solid land traversed by steam power, and intelligence communicated by electricity. Truly this is almost a miraculous era. What is before us no one can say, what is upon us no one can realize. The progress of the age has almost outstripped human belief; the future is known only to Omniscience”

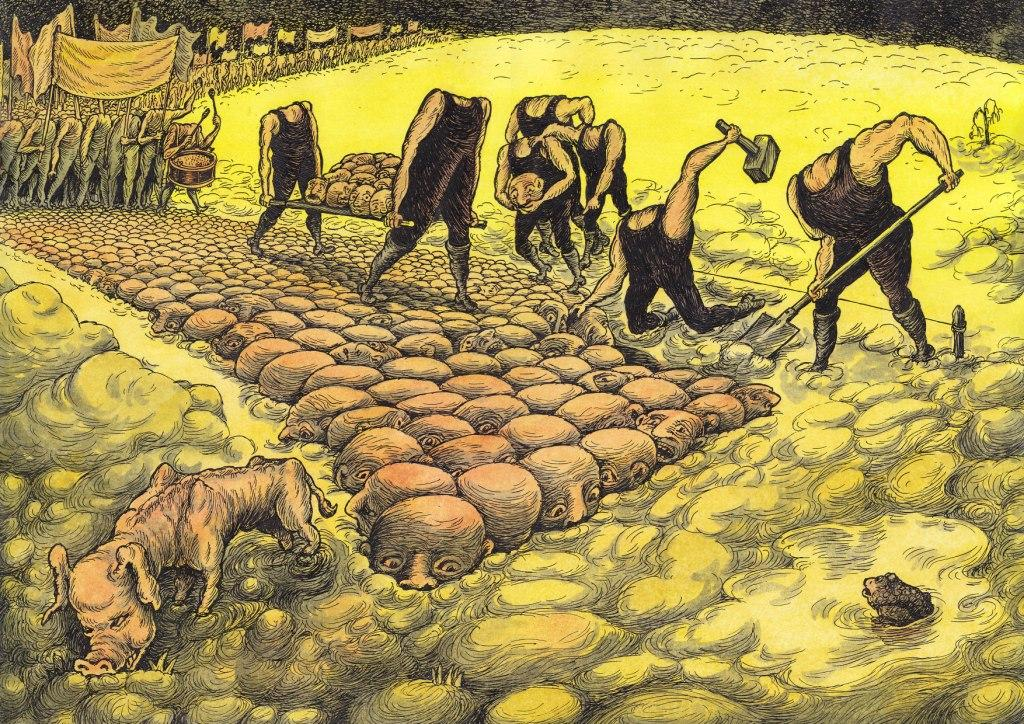

Thus, by the mid-19th century the vision had arisen of a new City of God on the horizon, to which technological innovation would inevitably take us. No human agency was required – the technology itself would dictate social improvement.

This view was, of course, challenged by the first and second world wars, which demonstrated that technological innovation could also empower evil – introducing the idea that innovation could be directed towards negative effects. In the early 1960’s, commencing with works like Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring”, an awareness emerged that, as well as a tool for intentional evil, technology could be a cause of negative side-effects which had not been anticipated.

The rapid development of new technologies and new capabilities means that, if we are to understand the ethical status of digital innovation, we must treat technology as a process rather than some static state.

Anticipating the future in a methodological manner is the realm of future studies, or futurology. A key paradigm of future studies is that the broad direction of travel can be discerned from a historical analysis of current trends.

The key trends dominating digital technology over the last 30 years have been fairly consistent, and are therefore generally considered characteristic of the nature of digital tech and its relationship with society.

These trends see rapid innovation having a strong social impact. Our current age is one of rapid digitisation. In addition to the digitisation of our intellectual and cultural capital, many cerebral processes, formerly the unique preserve of the human, such as city management, are being offloaded from humans to algorithms under the title of “big data.” New communication capabilities, such as social media, are combining with the digitisation of traditional formats, as newspapers and voice communication, go online. No aspect of the human world is immune to this process. Meanwhile, the urban landscape is increasingly monitored and governed by digital sensors and actuators, awash with digital wireless networks. The possibilities opened by the emerging field of smart materials will make the division between the digital and inert building material meaningless in the future.

The primary return derived from internet technology is in the form of data about people. This data is commodified (or monetised) through the provision of personalised services. The systems for gathering this data involve either notionally free services, such as search or social media, in which user activity is monitored, or the use of hidden tracking technologies. For example, Facebook uses the Like button to track people around the web, whether they are Facebook users or not, logged into Facebook or not, and for this reason the Like button is banned on commercial websites in some parts of the EU. Investigators have found most websites have an average of 20-30 such hidden trackers on them, while many have literally hundreds.

This technology is coupled with a system of rentier capitalism, in which we see restrictive terms of service combined with intellectual property protection to lock in users, restrict choice and stifle alternative business models.

These are key elements from Kindle’s terms of service:

“Kindle Content is licensed, not sold, to you by the Content Provider… and solely for your personal, non-commercial use…If you do not accept the terms of this Agreement, then you may not use the Kindle…We may change… or revoke your access to the Service at any time…”

In 2009, Amazon’s electronic rights to the works of George Orwell were challenged by MobileReference.com. In response, and before the case could be considered, Amazon removed 1984 and Animal Farm from all Kindle devices, without notice. In a later statement Amazon said they were merely removing “illegal books from customer’s devices.”

Rentier capitalism is a business model in which goods or services are not purchased, but rented for a recurring fee. In the context of digital technology, rentier capitalism displays two trends which create, and then reinforce, dominance of markets by monopolies. These are enclosure of digital commons coupled with enforced conditions for access to services.

Enclosure of digital commons takes place in two dimensions. Firstly, an expanding regime of copyright and intellectual property law is accompanied by the diffusion of software into a wider range of machines. The presence of software within machinery is held to introduce restrictions on use and repair of these devices. Amazon’s Kindle is a simple example. The same rules on copyright have been used by others, such as John Deere, the world’s leading tractor producer, to claim that it is illegal repair your own tractor.

No one owns the internet – its technology is public and cannot be copyrighted or patented. It was this avoidance of copyright and patent which made the technology so successful – anyone could use it and anyone who did use it could connect to anyone else using it. Previous attempts, such as Lotus Notes, had tried to achieve the same ends for over a decade, but under patented technology available only from a single provider, such as IBM or Microsoft. Those attempts failed because they were not open and so one software provider’s systems could not connect to their competitor’s systems. The Internet succeeds precisely because it is not protected by intellectual property regulations. Yet, services such as Facebook’s social media and Google’s search results algorithms are defended and extended through the use of closed silos of proprietary technology and hidden data practices. These sit on top of, and owe their existence to, those open standards and technologies which form of the material foundation of the Internet. This is seen by many as an enclosure of digital commons – the appropriation of public property for private advantage to the detriment of the opportunities for others. These “walled garden” as they are known (or “silos”) are protected through intellectual property and copyright regulation.

While renting does not necessarily involve restrictive terms of service, rentier capital as a phenomenon of digital technology always involves restrictive terms of service. By restrictive terms of service I mean those which offer no negotiation or alternative model; they are offered on a take-it-or-leave-it basis.

Digital rentier capitalism means other people own what is essential for your digital life, and will prevent you owning it. It means you are allowed to use it only under restrictive terms imposed without negotiation and without alternative. Every step possible is made to disempower the user.

How dangerous this lack of power can become is best illustrated by the recent case of pacemakers from St Jude Medical. Recently the US Food and Drug Administration took legal measures to force St Jude Medical to upgrade half a million wirelessly-enabled pacemakers in the USA. The FDA had been warning St Jude Medical for two years that these pacemakers were vulnerable to even the most amateur hackers, who could have killed their victims by accelerating or pausing the heartbeat. St Jude had resisted calling patients in for a 15-min upgrade process due to concerns over bad publicity. Similar scares have arisen recently over the ease with which car software, IoT home devices, and even internet-enabled toys, can be hacked. All of these devices are offered on a service, rather than a purchase, model.

“There is a fundamental lack of transparency about data broker industry practices. Data brokers acquire a vast array of detailed … information about billions of people … make inferences about them … and sell the information to a range of industries. All of this activity takes place behind the scenes, without consumers’ knowledge.”

– US Federal Trade Commission (2014) “Data Brokers: A Call for Transparency”

The modern Internet is based on the delivery of personalised services to individuals. Money is made by extracting value from the behaviour of these individuals. Personalisation is therefore incentivised towards stimulating behaviours in users from which profit can be drawn. Historically, the user response sought has been a positive response to advertising. As a result, personalisation has been tuned towards the delivery of advertising based on the personal characteristics of the individual consumer. This has generated a technology ecosystem for the gathering of personal data, the analysis thereof, and the delivery of services based on that analysis. While this has been focused on commercial advertising, some have realised that, just as one can advertise a commercial product, so one can advertise a political ideology. As the recent controversies with Facebook show, some have been using personalisation services to influence political attitudes. Meanwhile, experimental research into the search engine results effect shows that Google is capable of changing the outcome of national elections simply by the order in which search engine results are listed. All of this demonstrates the potential of personalisation services for political, as well as economic, domination within society. This power depends on epistemic control.

Epistemic control refers to two paired strategies corporations use to maintain their surveillance and personalisation power. Firstly, a policy of obscurantism in which their activities are hidden. Their internal practices, such as code and the algorithms by which data is processed, are hidden under the cloak of intellectual property. Meanwhile, personal data is gathered through the use of concealment. This includes technologies to overpower user resistance to being tracked, such as hidden tracking and deanonymisation services – the internet’s fastest growing industry. These efforts are coupled with mechanisms designed to cause epistemic blindness on the part of the consumer.

Epistemic blindness is achieved through obscurantism, such as making terms of service too long and too complex to understand (Twitter’s T&C’s run to 40,000 words). The power imbalance is further reinforced through the lack of alternative service models. Meanwhile the use of walled gardens prevents interoperability with other providers, and thus prevents the growth of a competition offering alternative models. The whole system is geared to monopoly domination.

The net result is that the user is forced to access essential services only if they agree to unknown data practices by unknown parties on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. They may never depart the service without the loss of everything they have accumulated within it.

I had stated earlier that understanding the ethical status today requires understanding the direction of travel modern digital technology holds.

The dominating trends of digital technology are the digitisation of the environment and the individual. Environmental digitization occurs through convergence, in which devices come to assume functions previously requiring purpose-built equipment. Hence the phone has absorbed the camera, the tape recorder, and many other technologies. Miniaturisation refers to the on-going reduction in the size of digital devices, to the point where it vanishes into the environment, becoming invisible. Thus we are now talking about smart dust – devices which can sense, process and communicate, but which are less than 1 millimetre across. Connectivity refers to the trend for a wider range of devices to have communication capabilities, including fridges, cars, houses, and clothing. Ubiquity refers to the results of these trends – the presence of digital technology throughout the environment, often invisibly, and spanning all living spaces.

The human is digitizing through the spread of carriable and wearable devices, and the rise of implanted devices, ranging from “traditional” devices such as pacemakers, to new developments such as smart skin which can wirelessly report infections and blood sugar levels.

All these technologies aim at the delivery of services personalised to the needs of the individual.

The net result is an ambient intelligence – a seamless digital environment perpetually watching and responding. At this point it no longer makes sense to talk in terms of individual devices, different types of data, or even different technologies. In terms of the human experience, these differentiations no longer matter. The individual is merely enveloped in a digital environment which surrounds and interpenetrates them.

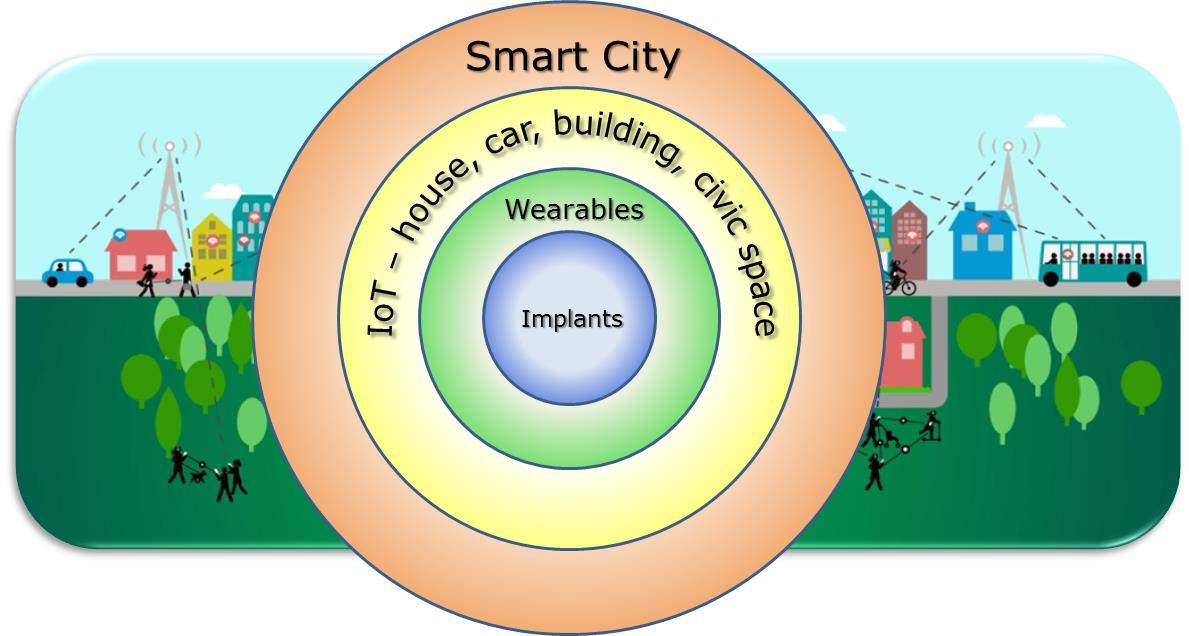

It makes more sense at this point to view digitisation as covering a range of overlapping zones. At the larger scale, the destination of civic services and infrastructure is that of the “smart city” – a built environment which uses this foundation and digital processes, to provide civic administration, such as automated management of traffic, electricity and sewage.

The Internet of Things represents the digitisation of the immediate space – the car, the house, the building, the street. It forms a “digital mesh” of sensors, actuators and similar individual devices. These devices communicate through networks which constantly change as people move about, known as “ad hoc” networking. Humans also constitute themselves as digital persons by carrying and wearing digital devices and through the increasing use of implanted bio-electronic devices, such as pacemakers.

The ethical status of this future destination is not determined by the technology or its functionality, but by the rules and systems under which it is provided. As we have seen, the value in the digital economy comes from the ability to personalise service delivery to the individual. This, in and of itself, is ethically neutral. The normative status of digital personalisation derives from the power dynamics under which it is run.

The terms and the circumstances under which we access almost all digital technologies are increasingly tuned towards disempowering the individual and empowering the corporation. Internet and digital technologies have the power to work horizontally within society; to connect individual to individual without the mediation of hierarchical power structures. Despite this, the use of rentier capitalism and epistemic control are tuned towards the disempowerment of the individual and imprisonment in a lifeworld shaped by, and for the benefit of, the corporation to the detriment of the user. The user’s sole function within this system is to respond in the way desired by the corporations.

Feudalism is a political system in which the individual is granted access to resources by an overlord on condition that they accept the conditions dictated by that overlord. Those are the conditions of access to most digital services, and so can be described as a state of digital feudalism.

A bio-electronic device embedded within your body is part of your body. The use of rentier capitalism on devices embedded within you means you no longer own part of your body – that part of your body is now owned by another. Slavery occurs when another owns your body. What is it when someone owns “part” of your body? I think it is still a form of slavery – a digital slavery.

There’s nothing inherently liberatory, or even positive, about technological innovation. In particular, the way in which it is operated will always have a larger impact on society than what it does. I have argued that the current model dominating innovation in digital technology is tuned to disempowering individuals in favour of traditional hierarchical capitalist corporations. I have suggested this is disempowerment is achieved through the use of rentier capitalism and epistemic control. These combine to restrict ownership, hide activities, and prevent the rise of liberatory alternatives.

Can we call it progress when the world we are building will put citizens under deeper control of corporations, reducing their rights and creating a high-tech feudal society in which corporate overlords dominate a race of digital slaves?

It is now 38 years since the internet was invented. The lesson of that time is that technology does not change anything – it merely empowers. That power can be used for social progress or social regression.

The direction of development of digital technology is towards ubiquity and personalisation. Ubiquity provides power. When personalisation is driven by commercial imperatives, it generates a drive to use personalisation to manipulate user behaviour for profit. When innovation is driven by such goals, it will inevitably develop systems for manipulation. Since the 1800’s there has been a recurring tendency in emerging technology ecosystems for consolidation and monopolisation, to the detriment of the greater good. Intellectual property regulation, essential service delivery via walled gardens of proprietary commercial technology, and hidden data practices have combined to create a digital landscape dominated by a few monopolies, who stand to become significantly more powerful in the future.

It is not, I am afraid, the purpose of my research to find solutions, ways of avoiding this outcome. However, I note the rising viewpoint that, as these are essential digital services, so they become public utilities. The concept of public utilities brings with it solutions to many of the issues I have discussed. At some stage before we fully enter into the world of ambient intelligence we will reach a point when digital services become essential. I therefore think it inevitable that, at some stage, many digital services will be regarded as public utilities. The question is whether we have reached that stage already?

Building a road to the future